Written by Meredith Pasahow

No matter what major you are in, there is an essay genre you will certainly come across at some point during your college career: the research paper. Whether this is math and science based or humanities based, every student will undoubtedly be required to write some kind of researched based essay. Oftentimes, the trickiest part is getting started with the research itself. So, in this post, we will explore some tips and tricks on how to make your research work for you.

The first thing to do is to select a database to start pulling research from. Google is all well and good, but it’s usually cluttered with clickbait and blog posts that are only tangentially related to your topic. For an academic or scholarly paper, I would recommend Google Scholar (scholar.google.com). This is a Google-based website specifically for peer reviewed articles, that automatically filters out all the internet detritus we tend to see floating around while we’re trying to find that one perfect source.

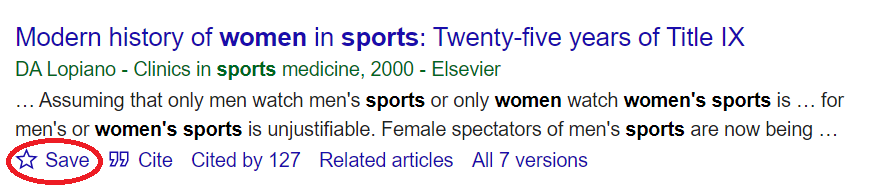

Google Scholar has a lot of fantastic features. For instance, say you’re researching women in sports as your topic and you find it. The perfect article for your paper. You love it, you want twenty more like it. Google Scholar has you covered.

You have two options to find more articles like the one you fell in love with. Cited By will give you a list of articles that have used your article as a source. Related Articles will give you more sources along the same lines as the one you like.

Need to do a bit of quick research but don’t have time to read everything you come across? No problem. Simply click on the star on the left-hand side…

…and the article will be saved to your library to read at your leisure. To find these articles later, click on the My Library tab and they will all be there for you when you are ready for them.

The one feature I do not recommend with Google Scholar, as with most sites, is the citation feature.

Though it is tempting to use citation machines like this, they are often out of date and do not have the current versions of MLA, APA, or whatever citation style you may need.

In terms of how to begin your research, I recommend starting broadly and narrowing your focus down from there. Sometimes, if we simply type our thesis question or main argument into a search engine, it’s too narrow for the algorithm to find anything for us. However, if we take a few steps back and look more widely at our subject, our research can often take us in unexpected directions. Sometimes we’ll find something we didn’t know we needed!

So, start, for instance, with something like “women in sports”, and then narrow it down to “women in sports Olympics” and then “when did women start participating in the Olympics”. If you’re still having trouble finding sources on your subject, try researching subjects adjacent to your subject. If you can’t find what you want on when women started participating in the Olympics, try searching “history of the Olympics” and going from there.

If you’re having trouble finding what you need on your own, I always recommend a trip to the library. We have incredibly helpful (and friendly!) research librarians who can get you pointed in the right direction. And after you’ve gathered all the research you need, it is much easier to grasp the writing of your paper.